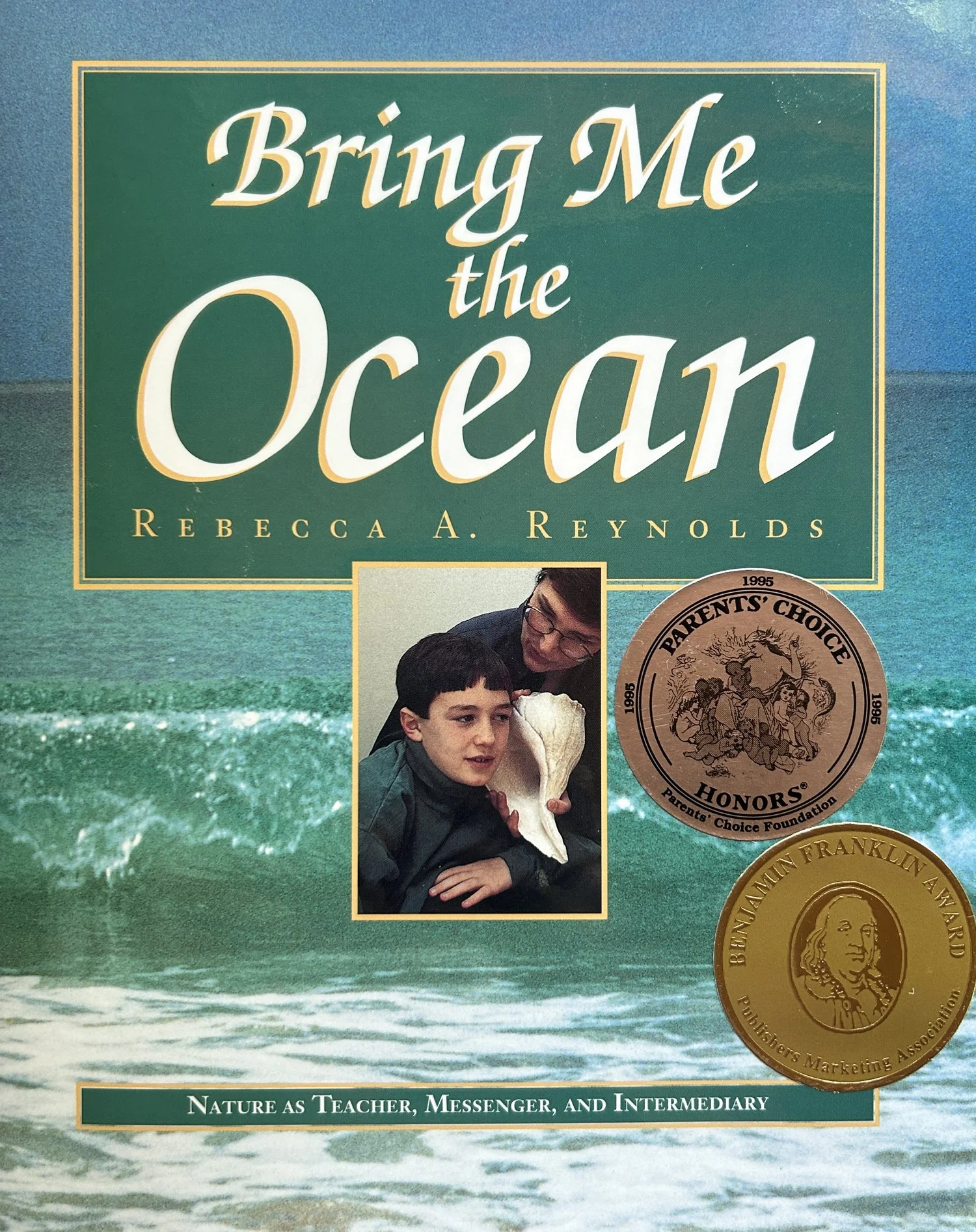

Reynolds’ essays, highlighted by photographs, share the healing gifts evoked by a segment of meadow or the sight, texture, and smell of the ocean. —Booklist

Japanese translation 1995

2 audio cassettes

Bring Me the Ocean: Nature as Teacher, Messenger, and Intermediary

Bring Me the Ocean (VanderWyk & Burnham, 1995) authored by The Nature Connection’s former executive director Rebecca A. Reynolds is a powerful collection of true stories that demonstrate the hope and renewal that can be found in interactions with the natural world. Poignant and sensitive, the stories come from bringing nature, animals, and the arts to people isolated from direct contact with the natural world, whether in a hospital, a nursing home, a residential treatment center, or other setting. Reynolds has created a book that quietly embraces the power and resilience of the human spirit. —The Nature Connection

AWARDS & FEATURES

Parents' Choice Silver Honors

Benjamin Franklin Gold Award in Psychology

Benjamin Franklin Gold Award in New Age

Semi-Finalist in Skipping Stones Honor Award Program

USA TODAY’S choice for Earth Day’s silver anniversary

NPR All Things Considered

PRAISE FOR BRING ME THE OCEAN

A wonderfully suggestive and entrancing collection of stories that tell us how a naturalist can connect with and help nourish vulnerable human beings—a gift to all of us.

—Robert Coles, M.D., Pulitzer Prize-winning author, and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard University

The words speak volumes; the photographs shimmer with insight.

—The Book Reader

-

Emerald Green Moss

Since the day of her admission to the nursing psychiatric ward, fifteen years before, Esther had not spoken.On this initial visit to the ward, Suzanne and Sarah brought a spring forest program. They, along with members of the site staff, went around the circle of people, offering pine boughs, moss, bunches of pine needles, and various animals to be observed, smelled, and touched.

Esther sat silent, as usual, withdrawn and inexpressive. She was unmoved by the great horned owl, and she didn’t even glance at the mice or the two dogs. Then Sarah came around with her palms full of thick green moss.

Reaching Esther, Sarah smelled the moss herself, saying, “Esther, would you like to smell the moss? It’s still wet with last night’s rainfall.” To everyone’s surprise, Esther responded. Reaching out with both hands, she took the moss and buried her face in the pungent, moist clump.

Then looking up, she exclaimed in a strong voice, “Emerald green moss!” She stared for an intense moment into Sarah’s eyes, before dropping back into her deep silence. Around Esther, her daily caretakers became silent too.

For fifteen years no one had found a way to break Esther’s silence or had heard her speak or had seen her look directly at another person. It was a moment of awakening for all of us. This moment supported and renewed the staff’s interest in Esther as a person, showing that there was indeed an avenue to reach her, even in her place of extreme isolation. Esther was not interested in the animals, but somehow the moss touched her senses.

This experience with Esther in our first year was a pivotal event. People often say, “Oh, it’s so wonderful that you bring animals in!” Equally important is bringing in the environment, interweaving layerings of materials and animals and stories, for these materials are the foundation for all the rest of life. Trying to explain why we lug rocks and water miles away to an institution is often difficult, but whenever we have a particularly strenuous day of gathering all the diverse materials and planning how to work them together into a comprehensive whole, we think of Esther, and know that it is worth the effort.

-

Clouds!

James had been institutionalized since he was nine years old. When we met him, he was almost thirty-seven. He was born with limited use of only his upper extremities and so relied on a wheelchair.For several years, he had refused speech therapy and was adamant about not participating in occupational therapy programs. He read constantly but spoke very little to others.

This was Animals As Intermediaries’ first of a series of visits to this chronic care hospital, and we arrived with an October program, bringing the theme of changing seasons, clouds, and winter winds. James sat, silent, giving us only the token presence of his body. He slumped down in his chair, staring at the floor. As the program began, Sarah talked about the kettling of hawks, their soaring and rising with wind currents, and about different types of clouds.

Looking up from his lap at one point, James saw the clouds Sarah was conjuring and became animated. In a tremulous bass voice, he called out, “Cumulus!”

At first as he told us about clouds, he was difficult to understand, but as we listened, he became even more animated, determined to communicate his knowledge of clouds. His knowledge, gained by extensive reading, had not been shared before. “Seeing” our clouds, however, sparked him to turn outward and share his inner knowledge. His inner clouds became a connection with the outer world. From that day on, James began participating actively, asking staff at the hospital when we would next arrive. When we were there, he spoke to the animals and, through them, to us.

One day, a ring-necked dove climbed gently onto his shoulder. He grinned. “Look!” he called out, engaging everyone. “Look! There’s a dove on my shoulder!”

Ten years later we received funding to go back for one visit to this same rehabilitation unit. I was amazed to see James with twenty other people waiting in the hall for the program to begin. I recognized him from the stories, and from some of our original video footage. I introduced myself to him, saying, “James, you know my mother. Ten years ago she came with doves to visit you.” In my mind I was seeing the video of the dove walking up his shoulder and then after a moment flying up around his head. It was poignant to meet him.

James lifted his head. Nothing in his eyes indicated that he had understood me. He looked blankly at me, strapped into his wheelchair. Then with his left hand James traced a walking path up his arm to his shoulder, patted his right shoulder and clearly said, “Dove, dove on my shoulder.” In a wide movement he threw his large hands into the air with a flutter, saying, “Dove flew.”

Ten years later. We had the same pair of ring-necked doves with us on this fall program. He held one cupped gently in his hands. Quiet.